Funeral Service in London: A Short History

Brian Parsons

London occupies an important place in the history of funeral service. The College of Arms, that managed funerals of the nobility until the eighteenth century still has its home in the City. Not far away the first commercial undertaker set up in business near the Old Bailey, around 1765. Most of the key funeral-related organisations can trace their origins to the capital; the Marylebone-based physician Sir Henry Thompson founded the Cremation Society of England in 1874, while the British Undertakers’ Association, the British Embalmers’ Society and the British Institute of Embalmers were all inaugurated here. Over the years, hundreds of firms of funeral directors have served families and London has provided the backdrop for many high profile funerals. This short history provides a glimpse into London’s fascinating funeral heritage.

The London Association of Funeral Directors

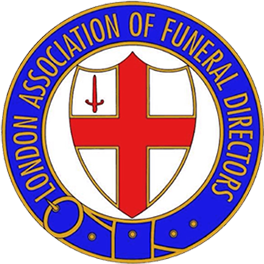

Whilst the British Institute of Undertakers can be identified as the first ‘modern’ trade association, it had only a short life in the closing years of the nineteenth century. In 1904 the London Funeral Furnishers’ Association (LFFA) was founded, followed a year later by the British Undertakers’ Association (BUA) with Henry Sherry from Marylebone as its first president. The capital’s undertakers were represented by the London Division of the BUA. In December 1935, the BUA was renamed the National Association of Funeral Directors, with its London Division becoming the London Association of Funeral Directors (LAFD).

The first president of the LFFA was William Knox, an undertaker from the Old Kent Road area, with Henry Kellaway of Dulwich as the secretary. Over the years the LAFD and its predecessors have represented the interests of its membership through negotiating with trade unions, central government and local authorities. It also has provided educational initiatives such as a work experience scheme and, more recently, the Certificate in Funeral Arranging and Administration. A feature has been the annual banquet and ball; with the exception of the two World Wars, this popular event has been held since 1907.

The chain of office was designed by Toye & Co in 1923; at the annual dinner that year Alderman Harold Kenyon used it to invest the incoming president, C Milne of Fulham.

Coffins

Provision of the coffin is central to the work of the funeral director. For many years coffins were hand crafted using elm and oak, but greater use of technology has been adopted the twentieth century and today the majority of coffins are machine constructed. Two factors have particularly impacted upon coffins. First, cremation authorities stipulated that easily combustible wood be used, along with coffin furnishings made from non-metallic materials. Secondly, the ravages of Dutch elm disease required the industry to seek alternatives, such as imported woods and non-solid boards like chipboard or medium-density fibreboard that could be covered in foil, veneer or cloth. Today a wide range of coffins and caskets are offered, including cardboard, wicker, bamboo and those decorated with images.

Care of the Deceased

Care of the Deceased

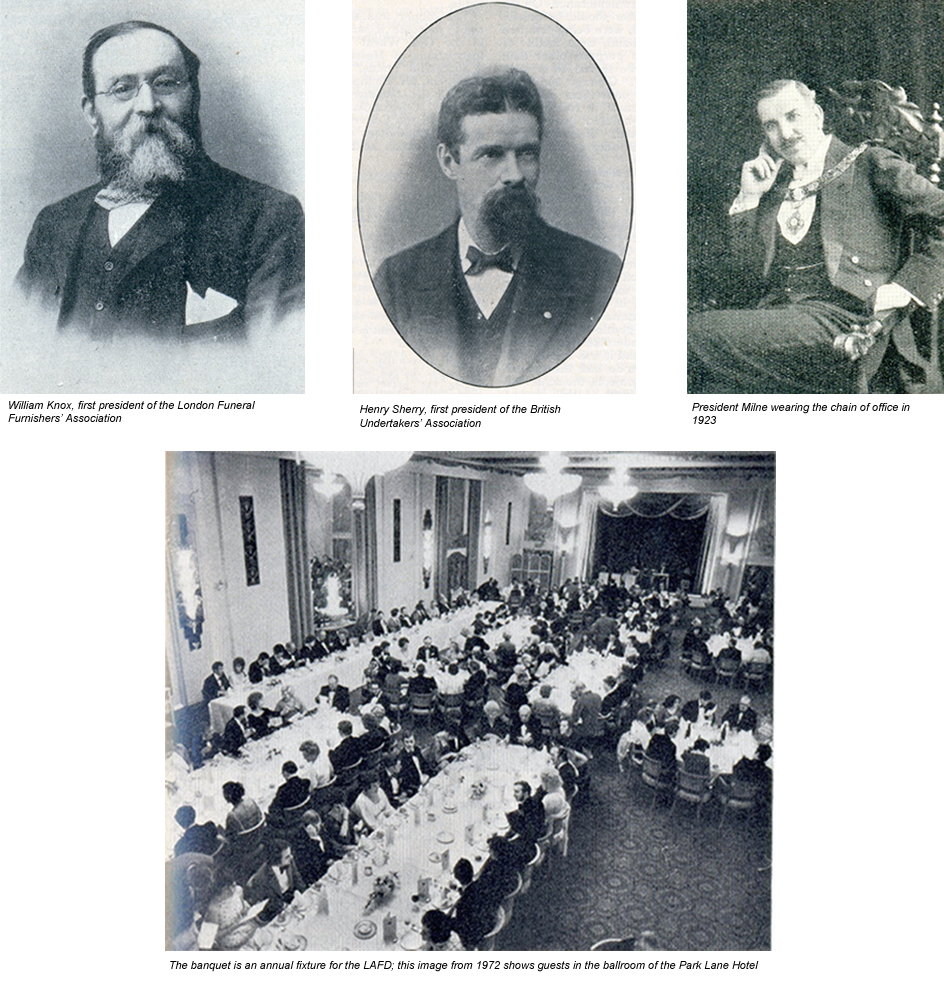

An important event occurred in 1900, when two American professors visited London to give funeral directors instruction in preservation techniques. After their departure, London-based pioneers such as Arthur Dyer, Albert Cottridge, George Lear and W Oliver Nodes actively promoted embalming by offering tuition to funeral directors. The latter was the first president of the British Institute of Embalmers that was founded in 1927, while George Lear ran both a trade embalming service and school.

In the early years most embalmments took place at home. However, during the interwar years death increasingly occurred in hospital and this encouraged the trend for the body to be transported to a chapel of rest to await the funeral. As funeral directors gained more responsibility for the decease, they provided fully equipped embalming theatres and mortuaries with refrigerated accommodation.

Transport

Due to their distance from urban areas and the impracticability of walking funerals, the horse drawn hearse was developed during the mid-nineteenth century to transport the coffin to the new private cemeteries located at places such as Kensal Green, Highgate and Nunhead. Most undertakers did not possess their own stable and hired from a carriagemaster, such as Henry Smith in Battersea or Dottridge Brothers near the City. Undertakers also made good use of the extensive rail network. to move coffins quickly and relatively inexpensively around the country. The service that ran from the London Necropolis Company’s private station at Waterloo to Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey was perhaps the most novel use of the railway. The coffin and mourners were conveyed directly into the cemetery using a branch line.

The motor hearse first made an appearance on London’s streets around 1906. Initially used for transporting coffins in a closed compartment, by the 1920s they were regularly appearing on funerals. Both forms of transport continued until the late 1940s, before the horse drawn hearse finally disappeared. However, their absence was only brief and much prominence was given to their return during the funerals of some notorious east end gangsters. The first motor hearses were, literally, the coffin compartment of a horse hearse secured to the chassis. As time has progressed the makes of funeral vehicles have largely reflected those adopted for domestic use: in the 1920s to 1940s Daimler, Austin and Rolls Royce, while Humber and Princess followed in the 1950s. A decade on Ford’s and Vauxhall’s were popular, while more recently Volvos, Jaguars and Mercedes have appeared. The Daimler DS 420 was held by many funeral directors to be the all-time classic funeral vehicle.

A Few Famous Funerals

Over the years, funeral directors in the capital have contributed to some of the most high profile funerals to have ever taken place in this country. The text accompanying these seven images outlines the involvement of some of the capital’s funeral directors.

In anticipation of the funeral of Lord Nelson on Thursday 9 January 1806, The Times predicted, ‘No procession that has ever taken place in this country will equal, in point of grandeur and pomp, that which will be displayed as the funeral of Lord NELSON.’ No more accurate assessment could have been written.

In anticipation of the funeral of Lord Nelson on Thursday 9 January 1806, The Times predicted, ‘No procession that has ever taken place in this country will equal, in point of grandeur and pomp, that which will be displayed as the funeral of Lord NELSON.’ No more accurate assessment could have been written.

Although the Garter King at Arms, Sir Isaac Heard, and the College of Arms were responsible for the funeral, aspects of the arrangements were subcontracted to the London firm of Banting and France. Constructed by a Mr Chittenden, the mahogany coffin was made from the mainmast of the ship Orient, the flagship of the defeated French during the battle of Nile. Mr Powell, an undertaker in Islington, designed the open state hearse with canopy.

Lord Nelson’s lying in state took place at Greenwich Hospital before a flotilla transported the coffin to Whitehall Stairs. From there it was taken to the Admiralty. On 9 January the procession made its way from Westminster via the Strand and Fleet Street where it entered the City at the Temple Bar gate before moving towards Ludgate Circus and finally to St Paul’s. After a service in the Cathedral the coffin was lowered into the grave located in the central space under the dome.

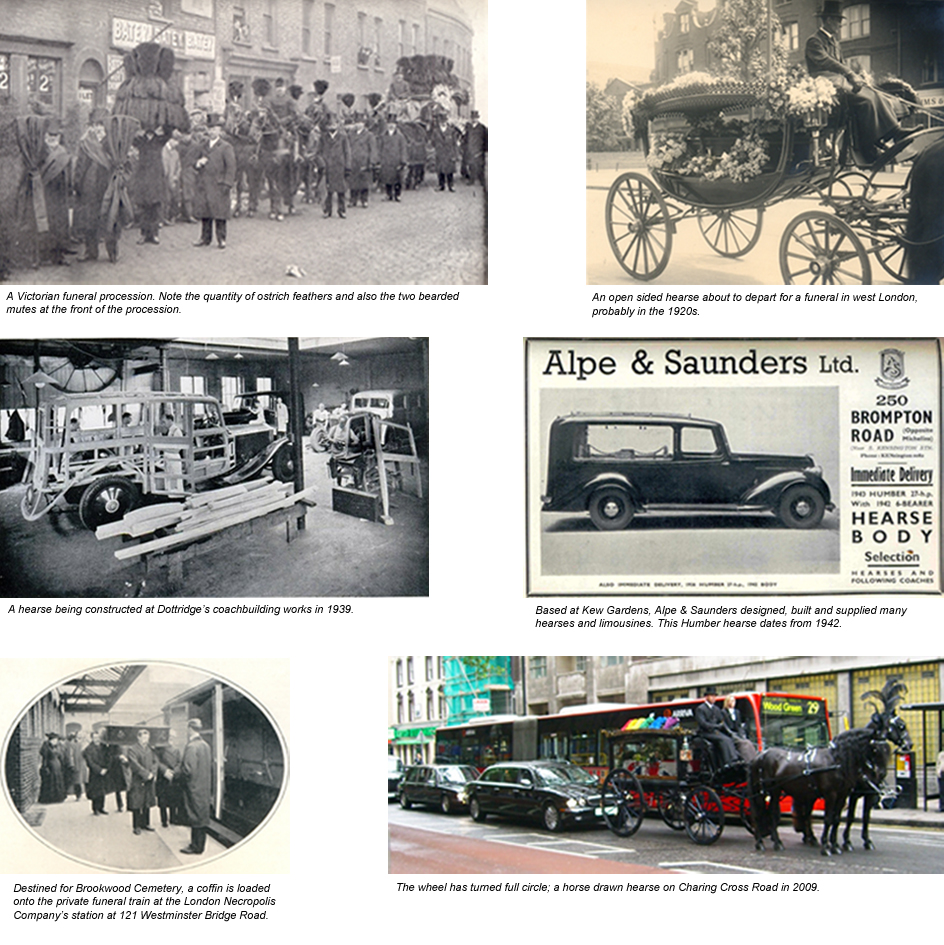

Queen Victoria died at Osborne House on 22 January 1901. Ten days later her coffin was transported from the Isle of Wight across the Solent to Gosport where it was taken by train to London. At Victoria station, twelve men of the Guards and Household Calvary placed the coffin upon a gun-carriage for the journey to Paddington (pictured here). The appropriately named Royal Sovereign locomotive then hauled the royal train to Windsor. After a service in St George’s Chapel, the coffin was moved to the Albert Memorial Chapel where it remained until the afternoon of Monday 4 February when interment took place next to Prince Albert in the royal mausoleum at Frogmore. The funeral furnishers W Banting of St James’s were engaged to assist with the funeral, with the equally historic firm of JD Field also making a significant contribution.

Queen Victoria died at Osborne House on 22 January 1901. Ten days later her coffin was transported from the Isle of Wight across the Solent to Gosport where it was taken by train to London. At Victoria station, twelve men of the Guards and Household Calvary placed the coffin upon a gun-carriage for the journey to Paddington (pictured here). The appropriately named Royal Sovereign locomotive then hauled the royal train to Windsor. After a service in St George’s Chapel, the coffin was moved to the Albert Memorial Chapel where it remained until the afternoon of Monday 4 February when interment took place next to Prince Albert in the royal mausoleum at Frogmore. The funeral furnishers W Banting of St James’s were engaged to assist with the funeral, with the equally historic firm of JD Field also making a significant contribution.

George V died on 20 January 1936 at Sandringham. His coffin was taken by train from Wolferton to King’s Cross, then to Westminster Hall for lying in state. W Oliver Nodes, first President of the British Institute of Embalmers, assisted Mr LV Weaving of William Garstin funeral directors in Marylebone with the embalming.

George V died on 20 January 1936 at Sandringham. His coffin was taken by train from Wolferton to King’s Cross, then to Westminster Hall for lying in state. W Oliver Nodes, first President of the British Institute of Embalmers, assisted Mr LV Weaving of William Garstin funeral directors in Marylebone with the embalming.

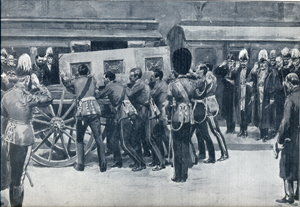

George VI’s funeral in February 1952 followed what had become an established format of lying in state at Westminster Hall then burial at Windsor. Desmond Henley of JH Kenyon was called upon to embalm the King and the firm assisted with other aspects of the funeral. This photograph shows the funeral procession at Marble Arch on its way to Paddington station.

George VI’s funeral in February 1952 followed what had become an established format of lying in state at Westminster Hall then burial at Windsor. Desmond Henley of JH Kenyon was called upon to embalm the King and the firm assisted with other aspects of the funeral. This photograph shows the funeral procession at Marble Arch on its way to Paddington station.

The funeral at St Paul’s Cathedral of the three policemen shot during a raid of a jewellery business in Houndsditch in December 1910. The incident led to the infamous ‘Siege of Sydney Street’. Sergeants Bentley and Tucker and Constable Choate were posthumously awarded the King’s Police Medal. The two sergeants were buried in the City of London Cemetery at Ilford and Constable Choate at Byfleet in Surrey.

The funeral at St Paul’s Cathedral of the three policemen shot during a raid of a jewellery business in Houndsditch in December 1910. The incident led to the infamous ‘Siege of Sydney Street’. Sergeants Bentley and Tucker and Constable Choate were posthumously awarded the King’s Police Medal. The two sergeants were buried in the City of London Cemetery at Ilford and Constable Choate at Byfleet in Surrey.

In October 1920 the London Centre of the British Undertakers’ Association was contacted by the Ministry of Works for assistance with the bringing home of the body of the Unknown Warrior. The president of the BUA was H Kirtley Nodes of John Nodes in Ladbroke Grove and together with the London secretary, the Revd John Sowerbutts, they accompanied the coffin to and from France. Wood for the coffin was sourced from the grounds of Hampton Court Palace and it was constructed at Ingall, Parsons, Clive & Co’s Forward Works at Wealdstone in north west London. The coffin was a ‘gift of appreciation’ to the nation from members of the BUA who each subscribed one shilling. As the coffin on a gun-carriage passed down Whitehall on the way to Westminster Abbey, George V pressed a button to release the flags covering the newly-constructed Cenotaph.

In October 1920 the London Centre of the British Undertakers’ Association was contacted by the Ministry of Works for assistance with the bringing home of the body of the Unknown Warrior. The president of the BUA was H Kirtley Nodes of John Nodes in Ladbroke Grove and together with the London secretary, the Revd John Sowerbutts, they accompanied the coffin to and from France. Wood for the coffin was sourced from the grounds of Hampton Court Palace and it was constructed at Ingall, Parsons, Clive & Co’s Forward Works at Wealdstone in north west London. The coffin was a ‘gift of appreciation’ to the nation from members of the BUA who each subscribed one shilling. As the coffin on a gun-carriage passed down Whitehall on the way to Westminster Abbey, George V pressed a button to release the flags covering the newly-constructed Cenotaph.

‘Incense in Kingsway’ was the headline in the Daily Sketch describing Father Arthur Stanton’s funeral procession. A faithful curate who ministered to the poor for over fifty years, his coffin, headed by a thurifer and churchwardens, was wheeler on a bier by fellow clergy from St Alban the Martyr, Brook Street, Holborn, to the Necropolis Station at Waterloo. At 2.30pm on 1 April 1913 a special train carried the coffin to Brookwood where a crowd of over 1,000 had assembled for his interment in the church’s own section of the cemetery.

‘Incense in Kingsway’ was the headline in the Daily Sketch describing Father Arthur Stanton’s funeral procession. A faithful curate who ministered to the poor for over fifty years, his coffin, headed by a thurifer and churchwardens, was wheeler on a bier by fellow clergy from St Alban the Martyr, Brook Street, Holborn, to the Necropolis Station at Waterloo. At 2.30pm on 1 April 1913 a special train carried the coffin to Brookwood where a crowd of over 1,000 had assembled for his interment in the church’s own section of the cemetery.

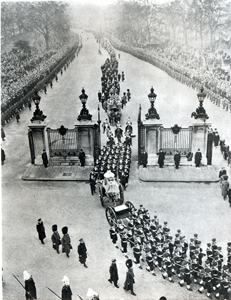

Dr Thomas John Barnardo was born in Ireland in 1845, and his name is still remembered today. Working in the East End during a cholera epidemic he procured a room in Stepney and stared to teach ‘rough, ragged boys of the district’. Homes were established in London, including the Girls’ Village Home at Barkingside. Following his death on 19 September 1905 his coffin lay in state at the Edinburgh Castle Mission Hall in Limehouse. A lengthy procession, headed by the band of the Stepney Boys’ Home, preceded the coffin to Liverpool Street station for the journey to Barkingside. After cremation, his ashes were buried beside the Children’s church. This image shows the scene at Barkingside station.

Dr Thomas John Barnardo was born in Ireland in 1845, and his name is still remembered today. Working in the East End during a cholera epidemic he procured a room in Stepney and stared to teach ‘rough, ragged boys of the district’. Homes were established in London, including the Girls’ Village Home at Barkingside. Following his death on 19 September 1905 his coffin lay in state at the Edinburgh Castle Mission Hall in Limehouse. A lengthy procession, headed by the band of the Stepney Boys’ Home, preceded the coffin to Liverpool Street station for the journey to Barkingside. After cremation, his ashes were buried beside the Children’s church. This image shows the scene at Barkingside station.